Out and about on the AAT … with Martin Marktl

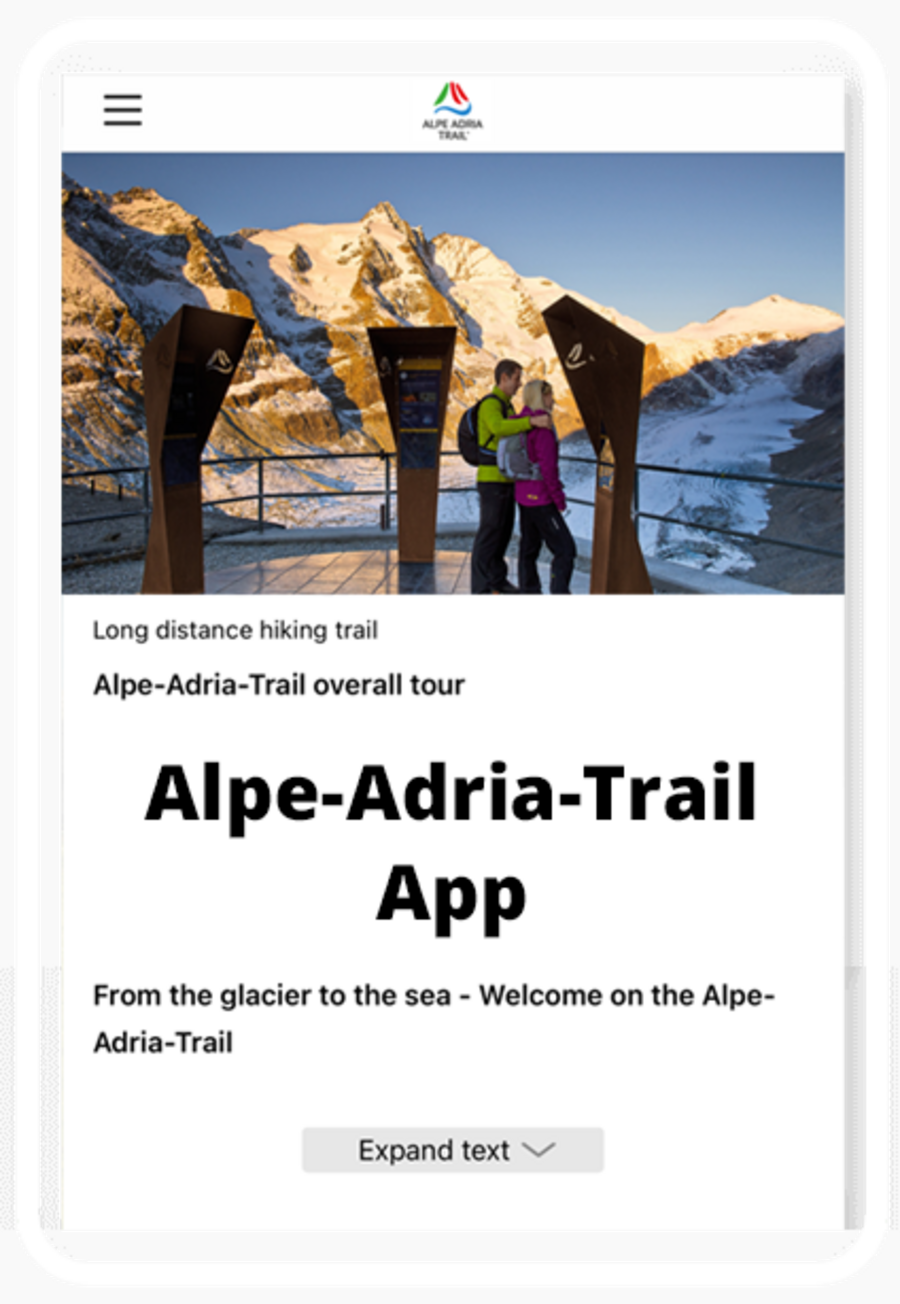

It was a glorious early summer day in June 2012. Astrid and I arrived in Muggia at around midday. We hotfooted it to this small sandy bay amidst the swaying boats, placed our rucksacks on the pier, and as the very first people to have walked the Alpe-Adria-Trail we dug our feet into the cool sea sand. Including the small extra circuit of the Dreiländereck where Italy, Austria and Slovenia meet, we had walked more or less exactly 800 kilometres, and we had been on the go for 44 days gross (although admittedly this also included 3 rest days).

A few years have gone by since a short press release in a German daily newspaper first made us aware of the Alpe-Adria-Trail. A brand new long-distance hiking trail, which was apparently going to lead right past our front door! As passionate long-distance walkers, we were immediately all for it. We talked about it for two evenings, and then our decision was made: once the season was over (at that time we had just taken out a lease on a small mountain lodge, which we also opened to the public in the winter), we would set off without fail.

Yet how were we going to do it? There was not a single marking on the entire stretch between the Glockner and the sea to show us how to get from A to B the way the inventor of the trail had intended. But with the help of the “AAT” pathfinders we got round this hurdle quite simply. They equipped us with current GPS data, and I was even permitted to tour the office on Lake Wörthersee in which at that very moment one of the few European three-country trails was being put together.

The rest is history. We immediately set about creating a hiking guide on paper for the publishers Bergverlag Rother. Another publisher, the Bruckmann-Verlag, had put the same idea into the back of Guido Seyerle’s mind, and he also set off at roughly the same time as us. We even managed to organise a meal together one evening at around that time when Guido was touring through Carinthia. Guido could no longer dispute the fact that we were the first people to walk the trail, but in return his guide was on the bookshelves earlier. So after 800 kilometres the score was one all.

The formal opening of the Alpe-Adria-Trail took place in June 2013. It goes without saying that in the meantime all the paths had been neatly marked, a booking centre had been set up, and numerous partner businesses had been won over to the idea. The message was clear: the Alpe-Adria-Trail is a route for pleasure hikers with an interest in culture, who want to complete their daily stages every evening in a pleasant atmosphere. Naturally this includes a wide selection of regional culinary specialities. And – particularly in the southern half of the trail – a good wine list. It makes no difference whether this is written in ornate lettering on deckle-edged paper, or freely recited by Francesco, because in all events, no one is going to walk through all the vineyards of the Collio or the Gorisca Brda without paying the vines along the wayside the attention they deserve!

But back to the first time it was walked. Two years now lie between us and our sandy feet in Muggia. And two years is really enough time to be delighted about reaching the finishing line early. Because truth to tell, in reality we were anything but the first people to walk the trail …

Let’s start at the top left, in the highest corner of Carinthia: back in prehistoric times the first traders certainly made their way along the Glocknerweg trail, where the starting point of the Alpe-Adria-Trail can be found today. They carried heavy wine casks northwards on their backs, and delivered fabrics, salt or tools to the south. So Astrid and I could already forget about the first stage – we were at least two thousand years too late for the gold medal.

On stages 2 to 21 we had to hand the laurels to Briccius, the Dane who reached our region exactly 1100 years ago via the kingdom of the Slavs carrying a bottle of Christ’s blood from Constantinople, and lost his life in an avalanche tragedy at the foot of the Grossglockner. Which is how Heiligenblut got its name, and the entire Carinthian section of the Alpe-Adria-Trail was walked for the first time – albeit in the opposite direction.

As far as Slovenia and Upper Italy are concerned, we know that there was an intensive trade in metal products there in the Middle Ages, which is hardly surprising as there are rich deposits of ore all around – and also enough rivers to power stamp mills or forges. So we are probably around a thousand years too late to claim the yellow jersey here too. The people who used to make their way through the Canal Valley with paniers weighing as much as 60 kilos would probably only raise a weary smile at our little trip.

So all we have left are the last few stages through the karst around Trieste. Maybe we could seize the glory of the moment here? No way. Excavations in Visogliano, a district of Sistiana (stages 31/32), show that this area was already bustling with life five hundred THOUSAND years ago. So that’s another dead loss …

A Spanish author once stated that “Caminante no hay camino, se hace camino al andar”. Or as Franz Kafka translated it: “Paths are made by walking.” Which also applies to the Alpe-Adria-Trail. It is true that there have always been people out and about along its paths. But up to now nobody had conceived of walking in this region as an experience that crosses borders and connects regions. The Alps-Adriatic idea as an element of the “Europe of the regions” has been around for a few decades, but I would assert that it is only the Alpe-Adria-Trail that has helped this “brand” to achieve a breakthrough. And it was the first to do so.